The Hal Launders Alice Launders Webb Pay it Forward Scholarship

March is the best month of the year to remember Harold Launders and his sister, Alice Launders Webb -the brother and sister for whom the Hal Launders Alice Launders Webb Pay it Forward Scholarship at St Lawrence University in Canton, NY was named.

Hal and Alice’s Birthday Cake in 1975

The siblings were both born in March, two years apart, in Greenwich Connecticut in 1908 and 1910 respectively.

They both attended St Lawrence University, Hal with help from the Charles Kelsey Gaines Fund graduating in 1932 and Alice as an older than average student graduating in 1937. Alice had worked several years before matriculating at St Lawrence which she accomplished with the help of her brother Hal. Both Majored in English.

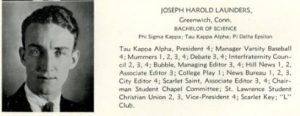

Yearbook Photo of Hal Launders

Alice died at age 68 on May 15, 1978, and on December 29, 1979, just one and a half years after her death, her brother Hal donated the first $10,000 to what was then known as the Hal Launders Alice Launders Webb Student Loan Fund.

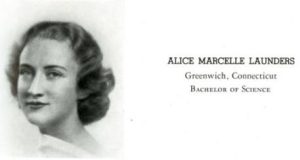

Yearbook Photo of Alice Launders Webb

In his letter to Peter Ticconi Jr– then Director of Capital Support Programs at St Lawrence -Hal made this promise,” This is the initial contribution. More will be forthcoming but not on any prearranged schedule. Just when circumstances permit, either from me or from my estate.”

In May 1982, W. Lawrence Gullick, acting from the Office of the President, sent Mr. Launders a letter to inform him that the Scholarship had been wrapped into a newly formed million-dollar financial aid endowment fund.

Hal died in 1996 with the promise of more donations still on the table.

In 2007 Emily Webb -Alice’s granddaughter and Hal’s great niece – decided mid-year that she wanted to transfer from a college in Boston to St Lawrence. David Webb (Emily’s father and my brother, Hal’s nephew and Alice’s son) and I, drove Emily up to St Lawrence University in Canton, NY. There we first met with the Development Office and asked about the already established Hal Launders and Alice Launders Webb Loan Fund for Emily and found out that this fund was now part of a much larger endowed fund with the Launders amount worth $100,000.

Emily Webb graduated in 2012 and by 2013 the Trustees of the Ruth and Hal Launders Charitable Trust were getting ready to make their first round of Board Level Grants. Eugenie Webb Maine (daughter of Alice and niece of Hal) reached out to Tom Pynchon, Director of Principal Gifts at St Lawrence, to inquire about extracting the $100,000 Launders grant from the endowment fund therefore making it possible for the Ruth and Hal Launders Charitable Trust family Trustees to sponsor a grant of a $100,000 to add to the existing $100,000 for a total of $200,000. Tom responded to this query in a letter to the Family Trustees on August 30, 2013, and explained that in the changing field of philanthropy most named grants had disappeared. He indicated that a great way to keep this named fund was to endow a Pay it Forward Scholarship. To quote Tom Pynchon, “I would like to make the following proposal for the family Trustees to consider: The Pay it Forward Scholarship. I think you will find this scholarship proposal unique and a difference maker for supporting scholarships. Not only does it help deserving students, but it also provides a mechanism to help teach the student recipients about philanthropy and giving back, just as Hal and Ruth Launders did with philanthropy.”

The $100,000 grant was delivered to St Lawrence University by the Launders Trust family Trustees in 2014 and since then five scholarships have been awarded. The recipients include the following: Matt Craighead ’16 – Fairfield, CT, Dillon Fitzpatrick ’18 – Darien, CT, Molly Wood ’18 – Salisbury, CT, Kylie Clancy ’20 – Glastonbury, CT, and Caitlyn Hone ’24 – Greenwich, CT.

The Market value of the Fund according to the latest activity report running from July 2022-June 30, 2023 is $232,437.

Here in Hal’s own words is “information about the only Launders left in our family.” “I was born March 18, 1908, in Greenwich Connecticut to Michael J and Alice Johnston Launders. My father came from Thurles in Tipperary and my mother from Prince Edward Island, Canada. I was the first child of that union (sister Alice was born two years later on 3/13/1910 ) but the 10th in the union of 2 families; my mother was a widow with 7 living children and my father a widower with 2 children when they merged.

My father was a building contractor who built residences and office buildings in the area, the most prominent perhaps is the Greenwich Town Hall which still stands today. My mother died when I was 11 years old and my sister Alice was 9. We were brought up by my oldest sister Mary, a school teacher who taught in Greenwich for 44 years. Mary broke her engagement to be married when her mother died to take care of Alice and myself and never married.”

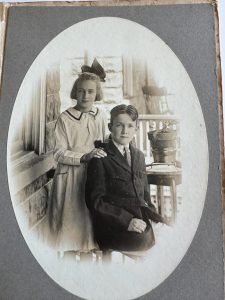

Hal and Alice as children in the summer of 1920 after their mother died.

Both Hal and Alice graduated St Mary’s Catholic High School in Greenwich and then went on to St. Lawrence University in Canton, NY. Hal was the class Valedictorian of his High School Class and went on to St Lawrence with merit scholarship support and then stayed on in the “north country” after graduation doing a variety of jobs, including wresting promoter, working for the Winter Olympics at Lake Placid and stringer for the New York Times to name a few in order to raise funds for his younger sister Alice to attend St Lawrence ; which she did living off campus and working on some of her brother’s projects while matriculating in three years.

Although the siblings experience at St. Lawrence was very different; Hal belonged to a Fraternity and was very active in student life while Alice kept her nose to the grindstone in order to finish in three years not really participating much in campus life; they both had very fond memories of St. Lawrence and maintained lifelong friendships from their time there.

In 1994 two years before he died Hal Launders donated $4,000,000 to establish the J Harold Launders Science Library and Computing Center.

Science Library and Computing Center at St Lawrence University

In the years following his death The Ruth and Hal Launders Charitable Trust has made several more donations to fund projects at St. Lawrence in Ruth and Hal Launders’ name.

Blog content provided by Eugenie Webb Maine

Eugenie Webb Maine

Eugenie is the niece of Harold Launders who set up the Ruth and Hal Launders Charitable Trust before his death in 1996. She has been a Launders Trustee since that time. Hal Launders is the brother of her mother Alice Launders Webb.

This program has proven life-changing for the youth who participate. Our graduates are now enrolled in colleges such as URI, Holy Cross, and Johnson & Wales. They are majoring in subjects like mathematics, computer science, and (believe it or not) neuroscience! We interview graduates one year after completing the program and the following quote is typical of what they tell us: “I’m at Rhode Island College studying graphic design. And I’m working part-time at Burlington Coat Factory in customer service. I would not have this job without Beautiful Day. I was a shy kid. I stuttered and my hands got sweaty and anxious. But when I went to the farmers markets I got to talk and I improved my communication skills and I’m not shy anymore. Now I’m talking to customers, like “How’s your day?”

This program has proven life-changing for the youth who participate. Our graduates are now enrolled in colleges such as URI, Holy Cross, and Johnson & Wales. They are majoring in subjects like mathematics, computer science, and (believe it or not) neuroscience! We interview graduates one year after completing the program and the following quote is typical of what they tell us: “I’m at Rhode Island College studying graphic design. And I’m working part-time at Burlington Coat Factory in customer service. I would not have this job without Beautiful Day. I was a shy kid. I stuttered and my hands got sweaty and anxious. But when I went to the farmers markets I got to talk and I improved my communication skills and I’m not shy anymore. Now I’m talking to customers, like “How’s your day?”

Recent Comments