Health Access Sumbawa (HAS) does malaria control and community development work on a shoestring budget in a roadless area of Sumbawa, a relatively poor Island in Eastern Indonesia. In 2015 we set out to control malaria in three remote villages for the price of a car. Remarkably, we succeeded. Our systematic program involves prevention measures such as hanging insecticide treated bed-nets in every home, then screening the population for malaria with a microscope and providing effective treatment. *

Five years ago the coastal farming village of Sili (where HAS is based) had every development challenge you could think of: No reliable road, not much electricity, no public water, no toilets, no employers, no health clinic, no shops, no schooling past the 6th grade.

Everyone wants the benefits of technology. We take our comforts for granted and sometimes forget that there are millions of people still living without such luxuries as running water or a toilet. Poverty is a major hurdle to overcome, but lack of money is not the whole story. Large well-funded development projects can fail just as spectacularly as small grassroots efforts. There are many potholes on the road to development.

What follows is a series of personal stories and lessons gleaned from working in Sumbawa at the grass-roots level over the past five years.

The significance of roads

Everything we do is made so much harder because Sili village in central Sumbawa has no reliable road connecting it to the outside world. Some might say the area is not exactly roadless. there is a dirt track that’s passable by a 4 x 4 truck or a strong motorbike on a dry day. But after a rain, not even a dirt bike can make it up the steep greasy mountain track to Tolo’oi. Walking out is your only safe option in any weather.

The lack of reliable roads in Sili Village is a real issue for its inhabitants.

A road connects a community to hospitals, schools, government services, buyers and sellers. Minor equipment failures such as a broken pull cord on a chain saw can delay projects for days or weeks in a roadless area. No reliable transport means the sick stay home in bed instead of going to hospital, students quit school after the 6th grade rather than go out for junior high, farmers sell their crop at lower prices to the only broker who comes to their village, people go hungry when they run out of food in their kitchen, and government planners fail to fund development projects because so few people have ever visited the community to see the problems.

Road construction is beyond the scope of Health access Sumbawa activities. Nevertheless, we needed a transportation strategy.

- We lobby elected officials for a road. I’ve found it’s most effective to emphasis the economic potential of the roadless area rather than complain about the hardship of living off the grid. I’m sure the Bupati (the area regent-an elected position) had never heard of Sili and it’s “best beach in Sumbawa” before I told him about it. The next year there was a plan (but no funding yet) to build a road.

- We develop relationships with strong skillful motorbike drivers to “taxi” HAS nurses and administrators around.

- We found a reliable fishing boat captain for water taxi. HAS supplies passengers with U.S. Coastguard approved life jackets.

- We bought two 29-inch mountain bikes for the clinic. Human-powered. Large wheels to handle rough terrain. Faster than walking.

Electricity- What went wrong with the ambitious solar grid?

A reliable source of electricity is another cornerstone of development. Even people in off-the-grid communities depend on cell phones and rechargeable battery powered lights these days.

In 2013 the government built a small community-based solar powered grid for Sili village. It was state-of-the art. Every home was connected by cable. The solar panels, inverters and batteries at the power company headquarters provided every home with enough power for a few lights, cell phone charging, and maybe a TV set for an hour each evening. the system even included street lights for the village.

The grid worked well for a year or two but by 2016 there were frequent periods of no service. One problem was cheating. Many people wanted to run a water pump or a TV. Homeowners soon figured out that they could bypass the metered connection to their house and take unlimited power directly from the pole. This caused the system to crash. Half the rate-payers stopped paying their modest $2 a month utility bill so the service technician stopped responding to calls.

There has been no electricity in the village for the past two years except at the power house. The three-room utility building has become a central charging station for phones and flashlights from all over the village. The room is a maze of power cords. People have decided that a central charging station is their greatest need for electricity. They’ve abandoned hope for a power grid that delivers electricity to their homes.

What went wrong? Perhaps the whole concept was too complex and, in the end, delivered too little power. The goal was to provide 300 watts per household, which is not enough to run water pumps, refrigerators, or power tools. People would still need a gasoline or propane generator for that. The grid never addressed that need.

With the benefit of hindsight, we can see that there were more appropriate solutions to meet the modest power generation goals of the project. Two alternatives are:

- Solar charging stations distributed around the village.

- A decentralized program that places mini solar panels on each home. This decentralized concept solves several of the fatal flaws of the centralized grid. It eliminates the problem of cheating, and pushes responsibility for maintenance down to the individual household level. When a system fails, only one house is affected.

Solar powered lights are a reliable source in Sumbawa.

Some of the personal solar power technology available today is astonishingly good. One of my favorites is Waka Waka Power +, a solar powered power bank and LED light the size of a hand phone. The light is bright enough for my old eyes to read the smallest type, and the battery lasts many hours. We also use cheap solar-powered security lights for general lighting. They activate by a motion detector, so you have to wave at the unit from time to time to keep it on, which is amusing at first but eventually becomes second nature. You can also hang the light from a string and spin it, creating a disco effect. Yes, we actually do that.

Toilets- The dangers of doing it badly.

Promoting Toilets is another goal everyone can agree on. What could possibly go wrong? A few years ago the village government gave three bags of cement to every house as a way to encourage people to build toilet houses. Unfortunately, there was no design guidance, no supervision, no follow-up. Most people sold their bags of cement. A few toilets were built, mostly too close to their water well. The septic tank design was faulty, and within a year raw sewage was visible on the surface of the ground.

A bad toilet is much worse than no toilet at all. It becomes a hazardous waste site. The traditional “jungle floor toileting” used by people in rural communities disburses the waste over a large area where it breaks down quickly. It is nature’s system. As we promote widespread use of toilets, we really must teach about the risks of bad waste water system design.

Health Access Sumbawa has built four toilets in Sili village in the past three years. One is a public bathhouse/toilet in front of our clinic. We consciously designed the building site so the septic tank/field could be at least thirty meters from any well. Our toilets are the only ones in Sili village to have running water. By the way, the primary school in Sili village has neither a toilet nor water.

A squat toilet is available in the public bath house in Sili Village.

Few people used the public bath house the first year, perhaps thinking it could not possibly be for them. By the second year it became so popular we had a problem supplying enough water. People started to complain that the water tank was often empty when they wanted to shower. We have since added a second tower and another 1,100-liter tank.

Pumping water while off the grid

It is challenging to provide running water to a community with no electricity or public water system. You need electricity to run a water pump, unless you are lucky enough to have an elevated water source such as a mountain spring which flows by gravity.

We dig or bore a well by hand, then pump water into a 1,100-liter water tank which sits on top of a tower. The tower is not expensive to build. We construct it from local timber which has been milled into columns and planks using a chain saw. Once the tank is filled, gravity provides the water pressure. This works fine as long as your taps are lower than the bottom of the tank.

There are three ways we could pump water without a power grid.

- Use a generator to power an electric water pump.

- use a gasoline-powered portable water pump.

- Use a solar or wind powered water pump.

Our first choice would be solar powered, because the fuel is delivered for free. Re-supplying propane canisters or gasoline cans is difficult and time consuming in a roadless area. It’s pretty common to run out of fuel, and resupply requires a full day of hazardous travel by motorbike. Solar water pumps move low volumes of water continuously whenever the sun shines. They don’t pump when the sun doesn’t shine. The pumps we found seem to work best when residential use can be paired with a trickle irrigation system for a farm. This is fine if you have the right situation. We’re excited about trying this pairing idea at our Beach Farm after we get the beach cottage built.

Solar pumps need a lot of storage capacity to perform satisfactorily in situations where demand for water peaks several times a day, such as a public bath house. For this application, a gasoline powered water pump is our most practical solution.

Advantages of portable water pumps-

- Move more water faster and with less fuel than a pump powered by a generator.

- Are affordable, rugged and easy to service.

- Can be transported on a motorbike. We plan to use one machine to fill tanks in multiple locations.

Regarding safe drinking water, we have found that the Sawyer 0.10 microns hollow membranes water filter is reliable and easy/cheap to maintain. (Back-wash by hand. No replacement filters required). We have been using these for four years now. One unit can filter enough drinking water for several households and costs under $100. We have not tried to filter muddy water. Fortunately, our water doesn’t have sediment.

Malaria control in three years- but no quick fix to sustain the gains.

As with all HAS initiatives, sustaining progress is the hardest part of our malaria elimination work. There is no inoculation, no immunity for malaria. People suffer repeated bouts in endemic areas. The only way to sustain a low infection rate is to fund an ongoing health service. You need to provide primary health care with a malaria component. This is a much bigger mission than we originally signed up for. But there is no other choice.

It turned out that HAS could step into this added role quickly and cheaply by partnering with the government health service. HAS already had one of the best health facilities in the region, the only clinic with running water. We hired the government nurses working in adjacent villages to come to Sili two days a week on a staggered schedule so our clinic is staffed and open 6 days a week. Primary health care at our clinic is free to the public, including medicines.

A woman in Sili Village bathes an infant in fresh water.

Travel by motorbike over dirt trails is tough for the nurses, but the added income provides powerful motivation. Government salaries are so low, the nurses are able to double their monthly income by working two days a week for HAS.

Small is beautiful

HAS is a volunteer organization with no paid staff at headquarters. We have a strategic reason to stay small. As social entrepreneurs, we want the enterprise to become self-sustaining one day. The goal of sustainability is more realistic if we keep our program in scale with the local economy. HAS is working toward a budget of $100,000/ year, which is significantly more than the government currently spends on health care in our expanded service area, which covers 50 kilometers x 15 kilometers and about 7,000 people.

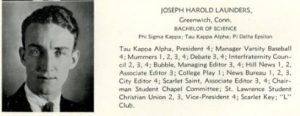

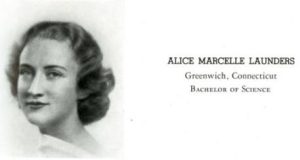

Our operating budget for the clinic is just $20,000 a year. A $15,000 challenge grant provided by The Ruth and Hal Launders Charitable Trust (RHLCT.org) was the catalyst HAS needed to increase its total annual budget to $55,000 last year. These new resources allowed us to significantly expand our service area for malaria, and pursue a range of initiatives designed to improve access to clean water, sanitation, and adequate nutrition.

A lesson in humility -The limits of technology

One morning we were leaving Sili for a meeting in the city of Macassar. When I tried to fill the kettle to boil water for coffee, no water flowed from the tap. The 1,100-liter water tank had been drained dry by early bathers at the community bathhouse. I went to start the water pump but we were out of gasoline. To top it off, when I tried to light the two-burner stove in the kitchen, there was no flame. the propane canister was empty. Someone joked that we had timed our departure from Sili almost perfectly.

For a few minutes we were baffled. Then the solution became obvious: We needed to revert back to the traditional way of doing things. Someone got a bucket and a piece of rope to take water from the well. Others built a cooking fire in the garden. Soon we were enjoying our campfire coffee and delicious grilled fish, fresh-caught during the night by our neighbor, a rare treat. We had been humbled by the limitations of our hard-to-sustain technology, and were reminded that sometimes the old ways are most reliable.

It’s not easy to design sustainable infrastructure which is as reliable as traditional methods. Poor people will not choose to cook with gas when firewood is free and readily available. A solar cooker is fine when the sun shines, but it’s useless on a rainy day, after dark or inside the house. A good gravel road is better than a thin asphalt one. Potholes in gravel can be patched with local materials. Potholes in bad asphalt become money pits.

We have learned that people often revert back to their traditional ways rather than fix technology when it stops working. People want technology, but it must be reliable, durable and affordable. Keep it simple and easy to maintain. Avoid products with “consumable” parts to buy, such as replacement water filters or disposable batteries.

A squat toilet with a properly designed and located septic system is an example of old technology that works great. The squatting position is already used by villagers and is anatomically preferable to sitting, the toilet flushes with just a dipper of water, there are no moving parts to break, and no consumables to buy such as toilet paper. Users wash their bum with water using the dipper. Hundreds of millions of squat toilets are in use throughout Asia.

Another old technology that has been updated is the mosquito net. Today’s nets, woven from polyester yarn, are less likely to get moldy than the old cotton ones. They can be impregnated with a safe long-lasting insecticide that immobilizes insects. We use WHO tested nets, Permanet 2.0 size 190 x 180 x150 cm. We can place three of these large nets in a home for about $30 to protect the entire family. Any tears or holes can be repaired with a needle and thread.

There have been many potholes in the road to development in Sili. We fill them in as we go along as best we can. The journey continues to be the adventure of a lifetime.

*For more information about the HAS project in Sumbawa, see RHLCT.ORG under Grants (Discretionary).

Contributed by Jack Kennedy. Jack is the son of a public health doctor who specialized in tropical medicine. He grew up in the South Pacific and South East Asia. Jack went on to pursue a successful career in international business, including activities in Indonesia. A lot of his time since 2014 has been devoted to Health Access Sumbawa in his roles as founder, president, and chairman.

This program has proven life-changing for the youth who participate. Our graduates are now enrolled in colleges such as URI, Holy Cross, and Johnson & Wales. They are majoring in subjects like mathematics, computer science, and (believe it or not) neuroscience! We interview graduates one year after completing the program and the following quote is typical of what they tell us: “I’m at Rhode Island College studying graphic design. And I’m working part-time at Burlington Coat Factory in customer service. I would not have this job without Beautiful Day. I was a shy kid. I stuttered and my hands got sweaty and anxious. But when I went to the farmers markets I got to talk and I improved my communication skills and I’m not shy anymore. Now I’m talking to customers, like “How’s your day?”

This program has proven life-changing for the youth who participate. Our graduates are now enrolled in colleges such as URI, Holy Cross, and Johnson & Wales. They are majoring in subjects like mathematics, computer science, and (believe it or not) neuroscience! We interview graduates one year after completing the program and the following quote is typical of what they tell us: “I’m at Rhode Island College studying graphic design. And I’m working part-time at Burlington Coat Factory in customer service. I would not have this job without Beautiful Day. I was a shy kid. I stuttered and my hands got sweaty and anxious. But when I went to the farmers markets I got to talk and I improved my communication skills and I’m not shy anymore. Now I’m talking to customers, like “How’s your day?”

Recent Comments